Practitioners

‘Physick, Pharmacy, or Chyrurgery … they are all three so depending one upon another, that they cannot be separated, and in times past they were all performed by one man, though now pride and idlenesse hath made them three professions; yet to say truly, whosoever professeth one, must be skilfull in the other two, else he cannot perform his work aright’.[1]

Joseph Du Chesne, Quercetanus redivivus, hoc est Ars medica dogmatico hermetica, ex scriptis Josephi Quercetani … tomis tribus digesta: quorum I. Ars medica mediatrix, II. Ars medica auxiliatrix, III. Ars medica practica. Operâ Joannis Schröderi (Frankfurt, 1648), vignette from engraved title page, depicting a physician inspecting urine.

This image of a physician, holding up a matula of urine to the light in order to make a diagnosis and prognosis for his patient, sick in bed at home, is perhaps stereo-typical of our image of early modern practitioners. Uroscopy had been one of the methods employed by physicians since the Middle Ages and it remained a wildly popular diagnostic technique (at least among the general public), and also as a symbol of the medieval physician’s art. As an image it continued to be a signifier for early modern physicians but throughout the period debate increasingly focused on just who was holding the glass and whether he was an academically-educated learned physician, for the early modern period witnessed a challenge to the traditional role of the learned physician, from a number of fronts. Their response may be seen in the rise of colleges of physicians across Europe, which, in effect, were defensive bastions of physicians’ privilege, designed to bolster the practice of medicine by early modern physicians against increasing encroaches by other medical practitioners, who sought to employ not only old techniques such as uroscopy but also new treatments. The challengers included other licensed medical practitioners such as apothecaries, surgeons, ecclesiastically licensed mid-wives, but also unregulated actors, such as women (involved in health care primarily though not exclusively in the home), and un-educated ‘quacks’ or ‘empirics’.[2] With the growth of print and the commoditization of medicines, the early modern medical marketplace became an intellectual battleground between a host of competing practitioners.[3]

Worth was clearly interested in the vociferous debates in early modern Europe concerning who should be allowed to practice medicine and what type of medicine should be practiced. While physicians, surgeons and apothecaries might look to their licensing bodies for legitimation, the practice of medicine on the ground did not, as Brugis had noted, reflect a neat tripartite structure between learned physicians who prescribed medicine, apothecaries who dispensed them, and surgeons who concentrated on operations on the body. Boundaries between the professions were poorly defined and often diffuse – particularly in rural areas.[4] The early modern medical marketplace thus encompassed a wide variety of players, many of whom had never darkened the door of an university or been apprenticed to a trained apothecary.

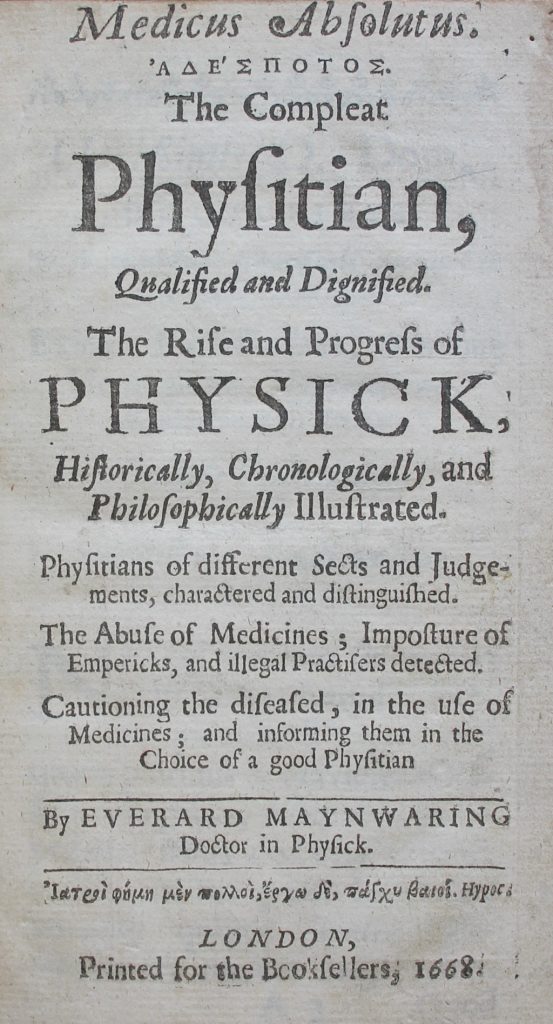

Everard Maynwaring, Medicus absolutus … The compleat physitian, qualified and dignified. The rise and progress of physick, historically, chronologically, and philosophically illustrated. Physitians … charactered and distinguished. The abuse of medicines … and illegal practisers detected. Cautioning the diseased … and informing them in the choice of a good physitian (London, 1668), title page.

Worth possessed an intriguing text which gives us a glimpse of the sheer complexity of the medical world of mid-seventeenth-century England. Its author was Everard Maynwaring (c. 1629–1713), a graduate of the University of Cambridge, who, after his graduation with a MB in 1653, had subsequently travelled widely, visiting America and spending a few years in Ireland during the Cromwellian period.[5] Indeed, he later claimed to have received his MD from the University of Dublin: ‘the Author travelling into Ireland; and being in Dublin, at the Time of a Publick Commencement: upon producing this Diploma from Cambridge; and performing such Exercises, as the Statutes of the University required: He proceeded Doctor’.[6] He returned to Chester in 1657 and subsequently moved to London after the Restoration. This move was accompanied by a major shift in his thinking: he turned his back on Galenic medicine, and became a keen advocate of chymical cures – cures which he offered himself. Indeed Maynwaring’s radical new departure was to argue that learned university-trained physicians should prepare their own medicines – thus cutting out the apothecary and, in his case, providing a welcome income stream.

Maynwaring’s text is interesting because it introduces us to a variety of medical practitioners in mid-seventeenth-century London. He discusses not only various ‘sects’ of physicians but also ‘several Sorts of Chymists’; ‘The Chymical Emperick’; ‘The Practising Apothecary’; ‘The Rigid Galenist’; ‘The Galeno-Chymist’ before finally outlined his own conception of a ‘Compleat Chymical Physician’.[7] At the core of Maynwaring’s conception of a new type of physician was chymistry: ‘so necessary to a Physitian that he cannot be compleat without it; nay they will not allow him to be an ordinary competent Physitian if he be not exercised and knowing in this Art’.[8]

Maynwaring was aware that even among the growing cohort of chymical physicians, dissension was rife – indeed he himself outlined at least four factions: ‘The Shop Chymist, the Chymical Emperick, the Galeno-Chymist, the True Chymical Physitian’. His definitions, which sought to elucidate the crowded medical marketplace, show us just how splintered it was:

‘The Shop Chymist, he is Operator and Venditor; a maker and seller of Chymical Medicines in his Shop: The Chymical Emperick he is Operator and Practitioner; a maker and practiser with Chymical Medicines: The Galeno-Chymist, he is Speculator and Practiser; an approver or lover of Chymical Medicines, and praciser of them, but not operator; he does not make nor exercise himself in Chymical operations. The True Chymical Physitian, he is Speculator, Operator and Practiser. It is his study, exercise and practice’.[9]

Differences between the groups were not only due to their methods but also their training and the scope of their practice: For Maynwaring, ‘Shop Chymists’, like Apothecaries dedicated to the preparation and sale of Galenic medicines, were part of an apprenticeship system, a trade which involved the making and selling of medicines which were prescribed by physicians. They were not to be equated with physicians, chymical or otherwise, for ‘their business extends no further in Medicines then their Shop, where their Trade is: the practice of Physick belongs not to these’.[10] While they were ‘Chymists’ they were not, in Maynwaring’s view ‘Chymical Physicians’.[11]

The difficulty for Maynwaring was that he fell between the various warring groups: the College of Physicians, which had been established in 1518, looked askance at his suggestions and considered his practice dangerously close to that of ‘empirics’ and ‘quacks’. The Society of Chymical Physicians and the Society of Apothecaries were equally wary, for though Maynwaring had perhaps most in common with the former, not all agreed with his views, while the latter society had much to lose if his reform of medicine was ever adopted. Maynwaring’s attempts to define his ‘Compleat Physician’ as an academically educated gentleman, who employed assistants to produce his chymical cures, was a compromise that few of the factions were willing to accept.[12] In effect, he was fighting a losing battle on three fronts: challenging physicians, be they ‘rigid Galenists’ or ‘Galeno-chymists’, to become more involved in medical production; attacking the position of apothecaries who not only produced medicines but also provided practical medical advice; and undermining un-educated ‘chymical empirics’. His work is important for the window it affords us into the plethora of medical practitioners in seventeenth-century England.

The fact that Maynwaring appeared to share some characteristics with ‘empirics’ (a charge he would have stoutly repudiated), did nothing to aid his cause with his fellow physicians. As Porter has noted, terms like ‘quacks’ and ‘empirics’ usually reflect the prejudices of the people using the term than the professional abilities of their targets, but physicians’ contempt for ‘empirics’ was both philosophical, social and economic.[13] As Cook has emphasised, the professional authority of early modern English physicians was rooted in being both educated and gentlemen, characteristics which they argued lay at the basis of their authority and which were lacking in their opponents.[14] The problem for the physicians was that the ‘empirics’ were both populous and popular. English and Irish physicians might look to their royal charters, but patients were more impressed by a quick (and cheap) cure, and, as Cook notes, they were hearing more about such cures in printed handbills and newspapers which transformed the early modern medical marketplace.[15]

The debates over the status of professions and professional boundaries were very much a staple of Worth’s own lifetime. Sir Richard Blackmore (1654–1729), spoke for many main-stream physicians in the early eighteenth century when he complained in 1723 about the large number of ‘ignorant’ medical practitioners:

‘When I reflect on the great Number of these unfortunate Men, especially in Country Towns and Villages, that enter upon a difficult Profession, in which for want of Sagacity, and good Sense required on Nature’s part, they are unable to succeed, and are likely to be more detrimental than beneficial to their Patients, of whom they serve those best, whom them visit least; and when I consider likewise the Swarms of Empericks and ignorant Pretenders to the Knowledge of Physick, and compare them with the few, that are endowed with suitable Qualifications for the Cure of Diseases, I am doubtful whether the whole Faculty might not be spared without any Damage to Mankind in general. It is true that Courts and populous Cities are happy in this, that there are among them many learned, able and worthy Physicians, to whom the Sick may have recourse: But how small is their Number, when compared with all the weak and ignorant Doctors, Quacks and Mountebanks, that abound not only in the Country Towns and Villages, but likewise in great Cities themselves?’[16]

Henry Cope. Line engraving by G. van der Gucht, 1736. Wellcome Collection. Source: Wellcome Collection.

As a practising physician in early eighteenth-century Dublin, Worth would have been well-aware that beyond the physicians licenced by the King and Queen’s College in Dublin (RCPI), and the surgeons and apothecaries validated by their guild, there were other practitioners at play.[17] Quite apart from his own experience he needed only to look at his copy of Henry Cope’s Medicina vindicata … (Dublin, 1727), a very revealing text on the subject of medical authority in early eighteenth-century Ireland.[18] Cope, a Fellow of the College, dedicated his book to the ‘President, Censors and Fellows of the King and Queen’s College in Dublin’, and was writing in the aftermath of a 1725 parliamentary debate on the subject.[19] He was keen to examine what earlier authorities had said on the contested matter of who should be responsible for bleeding and purging. Rather unusually, he provided his readers with a short list of his sources – a list that blends ancient Greek authorities such as Hippocrates, Galen; Roman authors such as Aulus Cornelius Celsus (1st century); Byzantine writers such as Alexander Trallianus (c. 525–c. 605), Aëtius of Amida (6th century), and Paulus Aegineta (7th century); sixteenth-century medical writers such as Jean Fernel (1497–1558), Jacques Houillier (d. 1562), Prospero Alpini (1553–1617); seventeenth-century authorities such as Thomas Willis (1621-75), Thomas Syndenham (bap. 1624, d. 1689), Giorgio Baglivi (1668–1707), and Bernardino Ramazzini (1633–1714), with more contemporary writers such as Daniel Le Clerc (1652–1728) and the Newtonian physician John Friend (1675–1728).

Cope’s text is not only of interest because it gives us a glimpse of the type of authors considered to be authorities on the subject of medical practice, but also for the insights it (perhaps unintentionally) provides as to the widespread use of domestic medicine (medicine ‘at home’), which he considered to be rife among the lower classes. He bemoaned that:

‘And it is very observable, that the more ignorant every Man is in the Profession he was bred to, or the Station of Life he is placed in, the more he is inclined to dabble in Matters of Physick; and I might likewise add, the more likely he is to meet with Encouragement from almost all Sorts of People’.[20]

Cope blamed the development on the example of non-licenced practitioners whose dangerous behaviour had undermined the medical practice of physicians by raising ‘Calumnies’ against it. He argued that the opponents of the 1725 ‘Physicians Bill for regulating the Practice of Physick’ claimed that the implementation of bleeding and purging should not be restricted to physicians alone but that non-licenced practitioners should also be allowed to tend patients for the public good.[21] Using his sources, he sought to prove that both ancient, medieval and contemporary writers were all in agreement that the bedrock of ‘all regular modern Practice’ (i.e. bleeding and purging), were the preserves of physicians alone.[22]

Cope blamed vernacular translations of the texts of the famed English physician, Thomas Sydenham, for the growth in bleeding and purging by either un-licensed practitioners or, indeed, in the home: ‘It must be confessed that Dr. Sydenham’s Works by being translated into English, have in great measure contributed to this Error, for by this Means he is become the common Refuge of Valetudinarians, as well as of those who quack with others’.[23] While a careful reading of Sydenham would enable his readers to ‘make themselves Masters of his, and all true Practice in Physick’, a cursory reading, by an unlearned practitioner, might well ignore important warnings given by Sydenham as to how, when and how much blood should be taken – decisions which depended not only on the health of the patient but also the experience of the physician.

In Cope’s view, the medical training of physicians was crucial: only by learning from the ‘regular and accurate Observations of the Nature, Progress and Cure of Diseases on Observations which not on their own, but all succeeding Experience hath confirmed the Truth of’ of predecessors (ancient, medieval and contemporary), could a physician hope to combat a disease.[24] He was, however, optimistic about medical care in early eighteenth-century Dublin:

‘this City was never at any time supplied with so many Physicians of Probity, Industry, Learning and Abilities, as at present; which must be attributed to the Agreement between the University of Dublin and the College of Physicians, in Pursuance of which young Gentlemen are obliged to undergo an Examination by the College, before they are admitted to take a Degree in Physick’.[25]

Cope’s emphasis on institutional training was typical of physicians, surgeons and apothecaries who each insisted on the symbiotic link between training and licensing. They did so because they were all too well aware that they were not the only practitioners in the early modern medical marketplace, a marketplace which was sometimes cutthroat. All three groups sought to distance their medical practice from that on offer in the wider medical marketplace: a marketplace which embraced a much wider community than those who were licenced by colleges of physicians or apprenticed to serving apothecaries.

Women

Saint Elizabeth of Hungary bringing food for the inmates of a hospital. Oil painting by Adam Elsheimer, ca. 1598. Source: Wellcome Collection.

The internecine warfare between physicians, surgeons and apothecaries which, as we have seen, was broadcast in lively published debates throughout the period, is fascinating, but it can overshadow the roles played by other actors in early modern healthcare. The medical debates between physicians, apothecaries and surgeons were turf wars in two ways – between members of these groups but also between licensed medical practitioners and other, un-official, actors in the medical marketplace. This is nowhere more true than in the case of women and healthcare in early modern Europe. As Fissell has argued, women ‘were central to health and healing before 1800’ but, as the vast majority were not allowed into universities and so could not train as learned physicians they could not, in turn, be accepted by the profession.[26] Only midwives, who were subject to examination, were considered acceptable purveyors of medical care, precisely because they were subject to ecclesiastical regulation.[27] The increasing importance attached to professional qualifications throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries ensured that women’s roles were often over-looked, fading into what Brockliss and Jones call the ‘medical penumbra’.[28] Recent work has sought to expand our understanding of the role of women in healthcare and as medical practitioners by using new sources and re-defining definitions of the medical marketplace.[29] As Strocchia argues, such an approach moves away from viewing female practitioners as being on the margins of medical practice and instead situates them ‘at the nexus of household medicine, emerging structures of public health, and the production of medical knowledge’.[30]

If male physicians, apothecaries and surgeons viewed themselves as the apex of professional medical care, the base of that particular pyramid was dependent on the healthcare provided by women, both in the home, in hospitals, and, indeed, in the wider community. If we move away from the printed diatribes between physicians and apothecaries and instead look at both administrative records and personal accounts, women begin to emerge into the medical spotlight: not only as healers in the home, nurses and administrators in hospitals, but also as people who played a vital role in public health by acting as ‘searchers’ during times of pestilence, and providing basic care to patients in the community.

We know from parish records that women were employed by parishes both as searchers for disease and as nurses to provide health care to patients within the parish.[31] Harkness, in her study of women and medical work in Elizabethan London, argues women’s roles went beyond this, suggesting that they were ‘central figures in the delivery of nursing, medical, pharmaceutical, and surgical services throughout the city as part of organized systems of health care’.[32] Women’s roles in early modern health care is visible not only in such parish records but also, by implication, in the diatribes by established (male) medical practitioners, who were often vocal on the subject of empirics and female practitioners (not always distinct groups)! The figures Harkness provides for London are striking: there were

‘just over 1,400 men and women who did medical work or community health work in the city of London between 1560 and 1610 (including apothecaries, midwives, carers for the sick in hospital and private settings, surgeons and physicians). Of that number, 70 per cent (927) were unlicensed, and approximately 30 per cent (305) of the unlicensed practitioners were women’.[33]

Harkness notes that despite the vocal attacks by male physicians less than 10 per cent of these female practitioners were prosecuted, and suggests that the debates between physicians and apothecaries, along with their pejorative comments about female medical practitioners, while enticing, distort our vision of what was actually happening on the streets of London: a community which embraced the health care given by such women, rather than condemned it.[34] What mattered most to early modern patients was less who was curing them but whether they were being cured. A herbal medicine dispensed by a female member of the family or acquaintance which worked might be more welcome than an expensive and sometimes dangerous chymical cure prescribed by a licenced medical practitioner!

Text: Dr Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library, Dublin.

Sources

Barry, Jonathan, ‘The ‘Compleat Physician’ and Experimentation in Medicines: Everard Maynwaring (c. 1629–1713) and the Restoration Debate on Medical Practice in London’, Medical History, 62, no. 2 (2018), 155–76.

Brugis, Thomas, Vade mecum: or, A companion for a chirurgion. Fitted for sea, or land; peace, or war. Shewing the use of his instruments, and virtues of medicines simple and compound most in use, and how to make them up after the best method. With the manner of making reports to a magistrate, or corroner’s inquest. A treatise of bleeding at the nose. With directions for bleeding, purging, vomiting, &c (London, 1681).

Blackmore, Sir Richard, A treatise upon the small-pox, in two parts. Containing, I. An account of the nature and several kinds of that disease, with the proper methods of cure. II. A dissertation upon the modern practice of inoculation. By Sir Richard Blackmore, Knt. (London, 1723).

Booth, Christopher, ‘Physician, Apothecary, or Surgeon? The Medieval Roots of Professional Boundaries in Later Medical Practice’, Midlands Historical Review, 2 (2018), 1–11.

Brockliss, Laurence, and Colin Jones, The Medical World of Early Modern France (Oxford, 1997).

Cook, Harold J., ‘Good advice and little medicine: the professional authority of early modern English physicians’, Journal of British Studies, 33 (1994), 1–31.

Cope, Henry, Medicina Vindicata : or, Reflections on Bleeding, Vomiting and Purging, in the Beginning of Fevers, Small Pox, Pleurisies, and other Acute Diseases (Dublin, 1727).

Cunningham, John (ed.), Early Modern Ireland and the world of medicine: Practitioners, collectors and contexts (Manchester, 2019).

Fissell, Mary E., ‘Women, Health, and Healing in Early Modern Europe’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 82, no. 1 (2008), 1-17.

Gorey, Philomena, ‘The episcopal and institutional regulation of midwifery in Ireland c. 1615-1828’, in Cunningham, John (ed.), Early Modern Ireland and the world of medicine: Practitioners, collectors and contexts (Manchester, 2019), pp 101–22.

Harkness, Deborah E., ‘A View from the Streets: Women and Medical Work in Elizabethan London’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 82, no. 1 (2008), 52–85.

Kelly, James, ‘Health for sale: mountebanks, doctors, printers and the supply of medication in eighteenth-century Ireland’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, 108C (2008), 75–113.

Kinzelbach, Annemarie, ‘Women and healthcare in early modern German towns’, Renaissance Studies, 28, no. 4 (2014), 619–38.

Leong, Elaine, ‘Learning medicine by the book: reading and writing surgical manuals in early modern London’, British Journal for the History of Science, 5 (2020), 93–110.

Maynwaring, Everard, Medicus absolutus … The compleat physitian, qualified and dignified. The rise and progress of physick, historically, chronologically, and philosophically illustrated. Physitians … charactered and distinguished. The abuse of medicines … and illegal practisers detected. Cautioning the diseased … and informing them in the choice of a good physitian (London, 1668).

Meyer, Victoria N., ‘Innovations from the Levant: smallpox inoculation and perceptions of scientific medicine’, The British Journal for the History of Science, 55 (2022), 423–44.

Pelling, Margaret and Charles Webster, ‘Medical practitioners’, in Webster, Charles (ed.), Health, medicine and mortality in the sixteenth century (Cambridge, 1979), pp 165–235.

Porter, Roy, ‘The language of quackery in England 1660–1800’, in Burke, Peter, and Roy Porter (eds), Language and society (Cambridge, 1987).

Strocchia, Sharon T., ‘Women and healthcare in early modern Europe’, Renaissance Studies, 28, no. 4 (2014), 496–514.

Wear, Andrew, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680 (Cambridge, 2000).

[1] Brugis, Thomas, Vade mecum: or, A companion for a chirurgion. Fitted for sea, or land; peace, or war. Shewing the use of his instruments, and virtues of medicines simple and compound most in use, and how to make them up after the best method. With the manner of making reports to a magistrate, or corroner’s inquest. A treatise of bleeding at the nose. With directions for bleeding, purging, vomiting, &c (London, 1681), p. 5.

[2] On the situation in early modern England see, for example, Wear, Andrew, Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680 (Cambridge, 2000), and Pelling, Margaret and Charles Webster, ‘Medical practitioners’, in Webster, Charles (ed.), Health, medicine and mortality in the sixteenth century (Cambridge, 1979), pp 165–235. On the situation in early modern Ireland, see Cunningham, John (ed.), Early Modern Ireland and the world of medicine: Practitioners, collectors and contexts (Manchester, 2019).

[3] On this process in early modern Ireland see Kelly, James, ‘Health for sale: mountebanks, doctors, printers and the supply of medication in eighteenth-century Ireland’, Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, 108C (2008), 75–113.

[4] Booth, Christopher, ‘Physician, Apothecary, or Surgeon? The Medieval Roots of Professional Boundaries in Later Medical Practice’, Midlands Historical Review, 2 (2018), 3.

[5] Worth owned a couple of books by Maynwaring: Morbus polyrhizos et polymorphæus. A treatise of the scurvy (London, 1666), and the above text, wherein Maynwaring sought to outline his radical proposals for a new type of medical practice.

[6] Barry, Jonathan, ‘The ‘Compleat Physician’ and Experimentation in Medicines: Everard Maynwaring (c. 1629–1713) and the Restoration Debate on Medical Practice in London’, Medical History, 62, no. 2 (2018), 158. Maynwaring’s claim is not substantiated in the matriculations lists of Trinity College Dublin.

[7] Everard Maynwaring, Medicus absolutus … The compleat physitian, qualified and dignified. The rise and progress of physick, historically, chronologically, and philosophically illustrated. Physitians … charactered and distinguished. The abuse of medicines … and illegal practisers detected. Cautioning the diseased … and informing them in the choice of a good physitian (London, 1668), Sig. (a3)v.

[8] Ibid., p. 29.

[9] Ibid., pp 36–7.

[10] Ibid., p. 37.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Barry, ‘The ‘Compleat Physician’ and Experimentation in Medicines: Everard Maynwaring (c. 1629–1713) and the Restoration Debate on Medical Practice in London’, 165.

[13] Porter, Roy, ‘The language of quackery in England 1660–1800’, in Burke, Peter, and Roy Porter (eds), Language and society (Cambridge, 1987).

[14] On this see Cook, Harold J., ‘Good advice and little medicine: the professional authority of early modern English physicians’, Journal of British Studies, 33 (1994), 1–31.

[15] Ibid., 22.

[16] Blackmore, Sir Richard, A treatise upon the small-pox, in two parts. Containing, I. An account of the nature and several kinds of that disease, with the proper methods of cure. II. A dissertation upon the modern practice of inoculation. By Sir Richard Blackmore, Knt. (London, 1723), pp viii-ix.

[17] See the chapters in Cunningham (ed.), Early Modern Ireland and the world of medicine for detailed explorations of medical practitioners in early modern Ireland.

[18] Worth’s copy is unfortunately one of the missing books in the collection. A copy is available online.

[19] Cope, Henry, Medicina Vindicata: or, Reflections on Bleeding, Vomiting and Purging, in the Beginning of Fevers, Small Pox, Pleurisies, and other Acute Diseases (Dublin, 1727), [p. 3].

[20] Ibid., p. 8.

[21] Ibid., p. 9.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid., p. 10.

[24] Ibid., p. 14.

[25] Ibid., p. 18.

[26] Fissell, Mary E., ‘Women, Health, and Healing in Early Modern Europe’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 82, no. 1 (2008), 1.

[27] On the regulation of midwives in early modern England see Pelling, Margaret and Charles Webster, ‘Medical practitioners’, in Webster, Charles (ed.), Health, medicine and mortality in the sixteenth century (Cambridge, 1979), pp 179; on the difficulties of tracking down early modern midwives see Gorey, Philomena, ‘The episcopal and institutional regulation of midwifery in Ireland c. 1615-1828’, in Cunningham (ed.), Early Modern Ireland and the world of medicine, pp 101–22.

[28] Brockliss, Laurence, and Colin Jones, The Medical World of Early Modern France (Oxford, 1997), p. 273.

[29] See, for the example, the articles in the 2014 special issue of Renaissance Studies, and Sharon T. Strocchia’s introduction to it: ‘Women and healthcare in early modern Europe’, Renaissance Studies, 28, no. 4 (2014), 496–514.

[30] Strocchia, Sharon T., ‘Women and healthcare in early modern Europe’, Renaissance Studies, 28, no. 4 (2014), 513.

[31] Harkness, Deborah E., ‘A View from the Streets: Women and Medical Work in Elizabethan London’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 82, no. 1 (2008), 67.

[32] Harkness, ‘A View from the Streets’, 52.

[33] Ibid., 58.

[34] Ibid.